Remembering the tragic 1935 WGC train crash

At 11.28pm on Saturday 15th June 1935, Wilson Bibby was arriving at the Cherry Tree restaurant in Welwyn Garden City (now the site of Waitrose) to take people home from a dance. Suddenly he heard a dull-sounding explosion, followed by a series of heavy grinding noises.

"I looked towards the station and saw a great red glare reflected in smoke and escaping steam. People came rushing out from the dance hall, many of them in evening dress to help shift the wreckage. They were met by a scene of horror, with dead and injured scattered along the track, and buried under tons of wreckage.

One of the most cool-headed workers was a woman, Dr Miall-Smith [subject of our previous article]. She had heard the fire alarm, was the first doctor on the scene, and worked all night to help the injured. We had to make improvised stretchers out of coach seats. Some of the people were terribly mutilated, and many of the rescuers were overcome with nausea. I saw a small black dog lying on one side of the track. Nearby was a bowler hat with a piece of wood sticking out of the dome. One of the most dreadful sights was that of a baby which had been crushed."

The crash was caused by human error: a signalman in the Welwyn box had mistakenly allowed two trains travelling north from King's Cross to enter the same section of track. The first, the 10.53 express to Newcastle, had been slowed by a signal and was leaving the station at 20mph; the second, which had started its journey at 10.58, ploughed into it at 50-60mph. The guard's van in the first train was pulverised, killing the guard and his dog instantly. The carriage in front of it was badly damaged but none of its occupants were seriously injured. The remaining nine carriages ahead were amazingly undamaged as they were modern with heavy duty couplings which kept them upright.

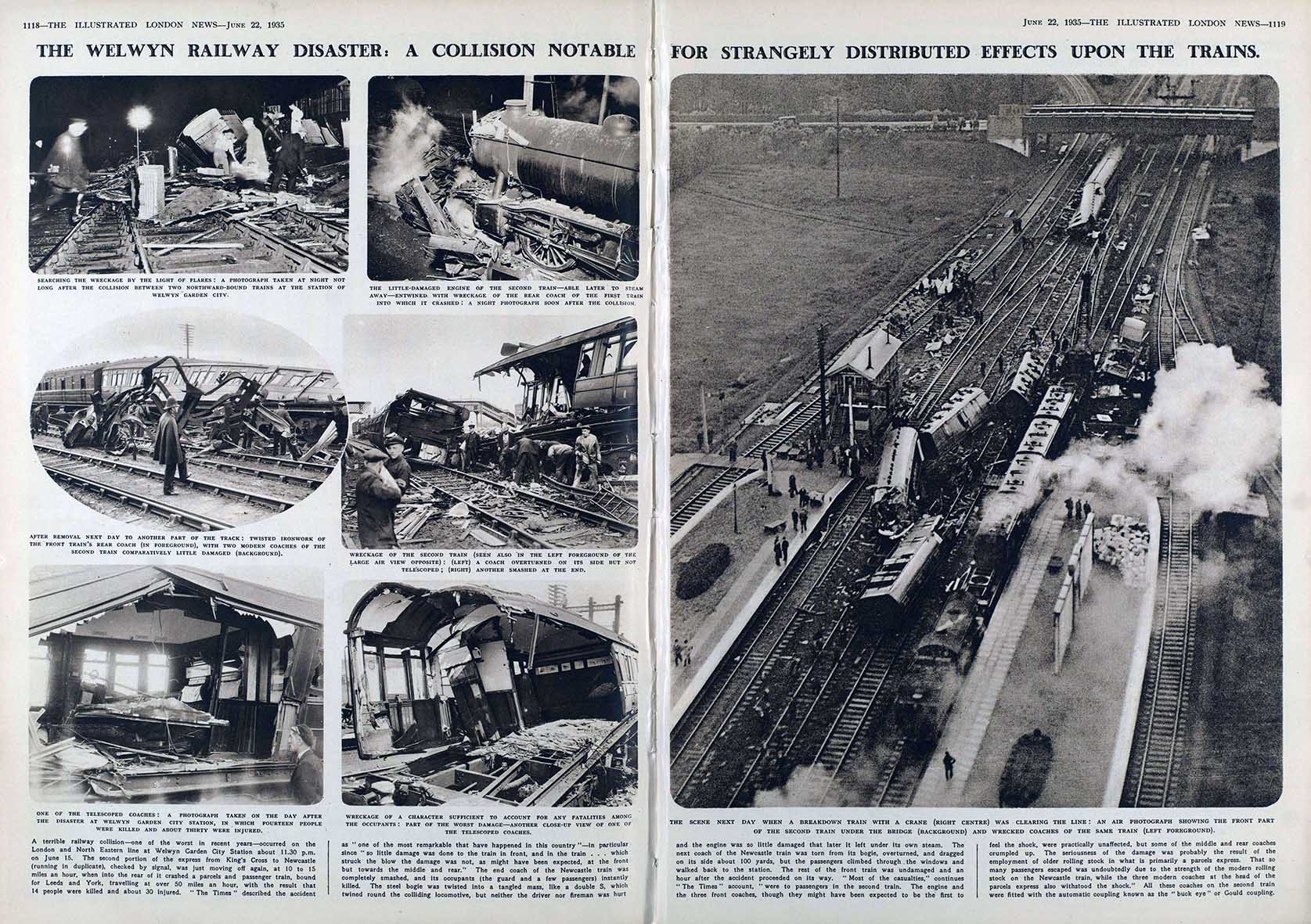

Above: A double page spread from The Illustrated London News reporting on the fatal collision at Welwyn Garden City on 15 June 1935 between two LNER trains, one from King's Cross to Leeds, the other from King's Cross to Newcastle. Picture courtesy Illustrated London News / Mary Evans Picture Library.

The first train was allowed to continue its journey after decoupling the damaged carriages. One of its passengers, Henry Robinson, had fallen asleep when it had left King's Cross and slept through the whole crash, only waking next morning and wondering where he was. The passengers in the second train were not so fortunate. Several of its carriages were of older design and were thrown off the track causing many casualties. The engine driver, Charles Barnes, survived because the locomotive was tremendously strong. It was able to move away under its own steam after the wreckage had been cleared the next day.

Fourteen people were killed, of all ages, in the crash. Several families suffered multiple losses: one poor man had to identify his mother, his wife, and their young son, who were among the dead. Twenty-nine people were seriously injured.

There were many acts of heroism that night, none more so than those of Dr Gladys Miall-Smith.

An enquiry found that the signalling system was poorly designed. It recommended changes which automatically prevented two trains being on the same section; this became known as the Welwyn Control and became a national standard. The jury at the ensuing inquest found the signalman not culpably negligent, and that the deaths were accidental.

This article by Geoffrey Hollis for the WGC Heritage Trust was first published in the Welwyn Hatfield Times on 16 Nov 2022.